Analyzing a Folksonomy

For our LIS 5703 the class together created a Folksonomy by tagging journal articles. This is the final paper examining the problems and accolades of that Folksonomy.

Part I Zotero and Joudrey and Taylor Chapter 10

Introduction

Upon initial inspection, the Zotero vocabulary created by the students of fall 2020 LIS5703-0001 looks to be a complete nightmare, but there are some redeeming qualities such as the direct order of phrases, the use of natural language, the light use of taxonomy, and the united purpose of helping each other. It does have many faults, but one must only look closely at recommended practices and the Zotero vocabulary to see its worth.

Authorized Terms

There are not many rules set for the Zotero vocabulary, but the few that were mandated should be followed. For instance, students expressed in fourteen different ways the phrase to indicate which contribute the item belonged to: “CON 2” “Con 2” “CON 4” “CON 5” “CON1” “Contribute 1” “Contribute 2” “Contribute 4” “Contribute 5” “contribute5” “contribute1” “Contribute3.” This lack of diligence means that when a student user tries to gather all the items under a certain contribute, they must select multiple phrases to do so leading to confusion. In this case, these phrases are synonyms, and “it is necessary to identify all the synonymous and nearly synonymous terms that should be brought together under a single authorized term” (Joudrey & Taylor, 2018, p. 484). Essentially, the class was given an authorized term for each contribute, yet some students did not follow the rule. This creates a bit of chaos and confusion for the end user.

Sequence and Form for Multi-word Terms and Phrases

There is no agreed upon way to write multi-word terms or phrases for the Zotero vocabulary creating a chaotic word list, but the overall use of direct order is redeeming. Capitalization of words in a phrase is all over the place, with sometimes the first word being capitalized, sometimes not, and sometimes second third or fourth words being capitalized, sometimes not. For instance: “mental health” “Mental Health” “History – Video Game – Development” “graduate” “Graphic Novels.” These inconsistencies in capitalization leads to a difficult end user experience as using the terms to search becomes cumbersome. Most of our Zotero vocabulary written is in direct order rather than inverse, with a few exceptions (“History – Video Game – Development” “Taxonomy – Development”). According to Joudrey & Taylor, direct order is the preferred way because “research has shown that few users think of inverted order but instead look for them in direct order” (2018, p. 486). So, in this way, our Zotero vocabulary is mostly satisfactory, with the exception of capitalization still causing confusion.

Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Initialisms

In our Zotero vocabulary there are thirty-seven instances of abbreviations, acronyms, and initialisms. Although there is no steadfast rule of how to handle abbreviations, acronyms, and initialisms the current thought is that “it is best to assume that they should be spelled out” when dealing with an unknown audience (Joudrey & Taylor, 2018, p. 488). Our audience, however, was not unknown so it begs the question, should the abbreviations, acronyms, and initialism stay? Uniformity is necessary, and the best examples of use in our Zotero vocabulary are “Text Encoding Initiative (TEI)” “Resource Description Access (RDA)” “Reader-Interest Classification (RIC)” “Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH)” and “Metadata Objects Description Schema (MODS).” Writing it this way, the user has access to both the fully spelled out term as well as the abbreviation, initialism, or acronym creating the highest chance of understanding and information retrieval.

Compound Concepts

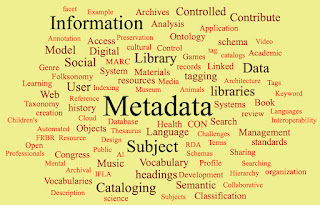

As seen in the word cloud above, the word metadata appears most frequently in our Zotero vocabulary, but if it appears the most, should there be more added to the phrase to indicate the topic of the item more clearly? This is the idea of compound concepts, when a term includes “multitopic concepts in the form of phrases” (Joudrey & Taylor, 2018, p. 489). The Zotero application and our tagging system, however, provides for this. Once “metadata” is chosen as the phrase to be searched, a list of articles appears. When an article is clicked, the user can see the 3 tags applied to the article creating a better idea in the user’s mind of what the article contains. The need for compound concepts, then, is eliminated by the 3 phrase tagging system implemented for this project. If a user knows they are interested in metadata, all they need do is look at the other tags of the item to understand more fully the content of the item. Otherwise, if compound concept phrases were used, there would need to be an agreement on “what forms these phrases should take” (Joudrey & Taylor, 2018, p. 489).

Part II Zotero and Contribute 3 Vocabularies

Wines.com contributed by A. Garner

The Wines.com wine varieties A to Z vocabulary is like our Zotero vocabulary in that both are arranged alphabetically by first letter in the phrase, but they are different because the Wines.com vocabulary follows a strict capitalization policy. For instance, “Cabernet Franc” “Asti Spumante” and “Gamay Beaujolais” all use a capital letter for the first letter of the first word and the first letter of the second word (Wines.com, n.d.). For the fields of Title and Subtitle, capitalization in AACR2 (Anglo-American Cataloging Rules, 2nd edition) says “in English, capitalize only proper nouns and proper adjectives” (Gorman, 2004, p. 150). For our Zotero vocabulary, capitalization is all over the place with multi-word terms sometimes having a capital for the first word, sometimes not, sometimes for the first word and second word, sometimes not, and even third and fourth words: examples “Distance Learning” “history review” “Institutional repositories” “schema for cultural resources.” Consistency in capitalization is key. Deciding what to capitalize and when, then setting a standard is best. The Wines.com vocabulary set a non-AACR2 standard, but they followed through whereas our Zotero vocabulary is all over the place with capitalization. As AACR2 suggests, only capitalizing proper nouns and adjectives would be best.

Wines.com could easily have chosen to group their wine vocabulary with red, white, rosé, etc. but chose not to, whereas our Zotero vocabulary is grouped at least by “Contribute 1,” “Contribute 2,” “Contribute 4,” and “Contribute 5.” In the case of our Zotero vocabulary, it is grouped by the above vocabulary terms which turns it from just a vocabulary more into a very lightly controlled taxonomy. The relationship of the “Contribute” terms to their accompanying entries would be one of parent to child. “All children in a genus/species relationship should be a type of the parent, (e.g., bronze is a type of metal)” (Harpring, 2020, p. 41). All the entries tagged with “Contribute 1” could be said to be a child of the parent “Contribute 1.” To see which entries are the child of a parent, all one must do is click the desired “Contribute” tag to display all the children. Wines.com chose not to become a taxonomy and instead strictly list wine names from A to Z with no interactive features. Using more advanced web page techniques, they could have included a drop-down menu to choose red, white, rosé, etc. to display wines of that variety. In this case, the Zotero vocabulary is more advanced than the Wines.com vocabulary.

Classification of Butterflies and Moths contributed by S. Hamm

Although the student generated Zotero vocabulary may look messy, there is something to be said about using natural language vs tight, controlled, technical language. Bogers and Petras find that “the natural or uncontrolled language in titles, abstracts or the full-text of a document and later in user-generated content (such as tags) is more varied and represents the author or user terminology” (2017, p. 18). On the flipside, we have the highly controlled vocabulary present on the webpage for classification of butterflies and moths, with such Greek derived words as “Dismorphiinae” “Eueides” and “Rhopalocera” (Enchanted Learning, 2018). The ability to understand what these technical terms represent is next to impossible if one is not an entomologist. However, the vocabulary developed by our class in Zotero is much more user friendly with terms being easy to speak, read, and understand. Some examples include: “Metadata Creation” “Keyword Searches” “User Behavior.” The contrast between these two vocabularies cannot be overstated, and with no supporting photographs and limited explanations the classification of butterflies page is not useful for anyone but the most avid butterfly experts, yet the website Enchanted Learning touts itself as targeted at school age children (Enchanted Learning, 2018). On the other end, our Zotero user generated vocabulary can easily lead to information discovery because the vocabulary words accurately represent terms understood by the target audience—our class.

As stated earlier though, the Zotero vocabulary is messy and could do with hierarchical organization to make the vocabulary more useful, much as the classification of butterflies does. Takehara, Harakawa, Ogawa, and Haseyama discuss using hierarchical structure, saying “the extracted hierarchical structure shows various abstraction levels of content groups and their hierarchical relationships, which can help users select topics related to the input query” (2017, p. 20252). In other words, using hierarchical relationships can help a person find the information they seek. For our Zotero vocabulary, there is a very limited hierarchical structure; the only one that could be said to be in place are the terms “Subjects” and “Metadata Application Profile.” Those 2 terms group the contributions into 2 groups, those applying to the metadata application profile and those applying to the subjects paper. The classification of butterflies, however, follows a much more rigorous structure of the taxonomy of animals; the webpage includes at the top the kingdom, phylum, class, and order with further breakdowns of suborder, subfamily, family, followed by one more unlabeled additional hierarchical relationship. This can help the onlooker quickly know much more information about a family, if they know the attributes of the subfamily or suborder. Our Zotero vocabulary could use more hierarchy to help students classify and find the articles, though it would be difficult to achieve without knowing more about each entry.

Beer Judge Guidelines contributed by P. Coleman

A stark contrast between our Zotero vocabulary and the beer judge guidelines is the introductory material. Our Zotero has one, whereas the beer judge guidelines has 8 pages of introductory material explaining the classifications to come. The official OWL 2 Web Ontology Language recommends the facilitation of “ontology development and sharing via the Web, with the ultimate goal of making Web content more accessible to machines” (W3C, 2012, p. 2). The goal of W3C is to “specify the definitions of terms by describing their relationships with other terms in the ontology” (2012, p. 2). The beer judge guidelines do this even in a static document, saying that the “categories (the major groupings of styles) are artificial constructs that represent a collection of individual sub-categories (beer styles) that may or may not have any historical, geographic, or traditional relationship with each other” (BJCP, 2015, p. x). Here we can see that the beer judge guidelines are drawing relationships where applicable, and recognizing that sometimes, that may not be possible. This is a preferable situation according to W3C that believes terms should have their relationships described (2012). Our Zotero list of terms makes only a slight attempt at this by grouping all the terms as either metadata application profile or subjects paper terms. More relationships between terms would improve the Zotero vocabulary, creating an environment of connection available for the user doing a search of terms. Further, the beer judge guidelines acknowledge their inability to connect everything, being sure to say that sometimes there are no connections, and it is at the authors’ decision to link terms though they are incapable of saying why. This kind of high-level admittance of both organization and faults is superb.

Another accomplishment of the beer judge guidelines is their ability to recognize that their system is not perfect, which fits with our Zotero vocabulary. Our Zotero vocabulary tries to bring together terms to help each other as classmates research for specific written outputs. That is not to say, in any way, that our vocabulary is exhaustive of the terms to be used for completing the metadata application profile or subjects paper, and it makes no claim as such. Similarly, the beer judge guidelines clearly say, “don’t believe that our guidelines represent the complete categorization of every beer style ever made – they aren’t” (BJCP, 2015, p. vi). Even academic ontologies should make similar claims, as did Jones, Coviello, and Tang, explaining that their systematic ontology of international entrepreneurship “is not definitive nor is it intended to be. Rather, we attempt to inventory, summarize, synthesize and interpret research in IE over the 1989–2009 timeframe” (2011, section 5). As mentioned before, this kind of admittance of fault with a system is essential, and if an introduction were written for our Zotero vocabulary then it must contain such a disclaimer.

The purpose of the beer judge guidelines is to help users gain needed information to judge beers; the purpose of our Zotero vocabulary is to help classmates gain needed information to write the metadata application profile and the subjects paper. As du Preez points out, in most folksonomies “users have different tasks and approach documents with different motives, and the documents are located in different cognitive contexts. They do not share a common indexing level” (2015, p. 36). However, for our Zotero project there was a known motive (helping other classmates find research) and a shared cognitive context (the class Information Organization). In this way, the Zotero vocabulary is not a true folksonomy. So, our Zotero vocabulary and the beer judge guidelines share that similarity; in that both were developed with a specific purpose in the mind of the author/s writing the vocabulary.

Conclusion

Our Zotero vocabulary may have its faults, but it did serve the purpose intended: to bring together a large variety of user generated tags to identify published items under certain concepts (metadata application profile and subjects paper) so that students may help each other research. Setting some additional rules in an introduction for capitalization and initialisms could go a long way to improve the search experience for users. All over though, the Zotero vocabulary served its purpose by providing help to fall 2020 LIS5703-0001 students find the needed sources for their work.

References

BJCP. (2015). Beer judge certification program: 2015 style guidelines. BJCP.org.

https://legacy.bjcp.org/docs/2015_Guidelines_Beer.pdf

Bogers, T., & Petras, V. (2017). Supporting book search: A comprehensive comparison of tags

vs. controlled vocabulary metadata. Data and Information Management, 1(1), 17-34.

https://doi.org/10.1515/dim-2017-0004

du Preez, M. (2015). Taxonomies, folksonomies, ontologies: What are they and how do they

support information retrieval? Indexer 33(1), 29-37. https://doi.org/ 10.3828/indexer.2015.5

Enchanted Learning. (2018). Classification of butterflies. EnchantedLearning.com.

https://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/butterfly/Classification.shtml

Gorman, Michael. (2004). Appendix I. In, The concise AACR2. (4th edition). (pp. 149-151). ALA

Editions.

Harpring, P. (2020). Introduction to controlled vocabularies: Featuring the Getty vocabularies.

Getty.edu. https://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/intro_to_vocabs.pdf

Jones, M., Coviello, M., & Tang, Y. (2011). International entrepreneurship research (1989-

2009): A domain ontology and thematic analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), pp.632-659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.04.001

Joudrey, D., & Taylor, A. (2018). The Organization of Information. (4th edition). Libraries Unlimited.

Takehara, D., Harakawa, R., Ogawa, T., & Haseyama, M. (2017). Extracting hierarchical

structure of content groups from different social media platforms using multiple social

metadata. Multimedia tools and applications, 76(19), pp. 20249-20272.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-017-4717-7

W3C. (2012). OWL 2 Web Ontology Language Document Overview (Second Edition). W3.org.

https://www.w3.org/2012/pdf/REC-owl2-overview-20121211.pdf

Wines.com. (n.d.). Wine varieties A-Z. Wines.com. https://www.wines.com/wine-varietals/

Comments

Post a Comment